DNS Encryption Explained: DoT, DoH, and DoQ for Network Engineers

Your DNS queries are visible to everyone between you and your resolver. Learn how DoT, DoH, and DoQ encrypt DNS traffic—with practical configuration and troubleshooting guidance for 2025.

The Privacy Problem Hiding in Plain Sight

Every time you type a URL into your browser, something happens before you see a single pixel of that webpage. Your device sends a DNS query—a small request asking "what's the IP address for this domain name?"—to a resolver somewhere on the internet. This process is so fundamental to how the internet works that most people never think about it. But here's the uncomfortable truth: by default, those queries travel across the network as plaintext, completely unencrypted, readable by anyone positioned to observe your traffic.

Think about what that means in practical terms. Your Internet Service Provider can see every domain you visit. The operator of that coffee shop WiFi you're connected to can build a complete profile of your browsing habits. Corporate network administrators can log every site employees access. Government agencies with network-level visibility can track citizens' online activities. And attackers who manage to position themselves between you and your DNS resolver can not only observe your queries but potentially manipulate the responses, redirecting you to malicious sites without your knowledge.

This isn't a theoretical concern or a problem that only affects people in authoritarian countries. ISPs in the United States and Europe routinely log DNS queries for analytics, advertising, and regulatory compliance purposes. Some inject their own content into DNS responses. Others sell aggregated browsing data to third parties. The DNS system, designed in the 1980s when the internet was a trusted academic network, simply wasn't built with privacy or security as primary concerns.

Fortunately, the networking community has developed solutions. Three encryption protocols now exist to protect DNS traffic: DNS over TLS (DoT), DNS over HTTPS (DoH), and the newer DNS over QUIC (DoQ). Each wraps your DNS queries in encryption, preventing observers from seeing what domains you're looking up or tampering with the responses. But they do so in different ways, with different tradeoffs that matter depending on your specific situation and goals.

Why This Matters More in 2025

The push toward encrypted DNS has accelerated dramatically over the past year. On January 17, 2025, the United States government issued an Executive Order titled "Strengthening and Promoting Innovation in the Nation's Cybersecurity," which includes a mandate requiring federal agencies to implement either DoH or DoT within 180 days. This isn't a recommendation or a best practice suggestion—it's a compliance requirement with a deadline.

For those of us working in enterprise environments, this executive order signals a broader shift that will eventually cascade into private sector requirements. If you're architecting network infrastructure today and not planning for encrypted DNS, you're building technical debt that will need to be addressed sooner than you might expect. Regulatory frameworks, industry standards, and customer expectations are all moving toward treating DNS encryption as baseline security hygiene rather than an optional enhancement.

The adoption numbers reflect this momentum. Current research indicates that approximately 13.7% of global DNS traffic now uses DoH, with that percentage growing steadily. Major browsers have enabled DoH by default for users in multiple countries. Operating system vendors have added native support for encrypted DNS configuration. The infrastructure exists; the question is no longer whether to adopt encrypted DNS but how to implement it in a way that aligns with your security requirements and operational constraints.

Understanding the DNS Resolution Process

Before diving into the specifics of each encryption protocol, it helps to have a clear mental model of what happens during a DNS lookup. When you request a webpage, your browser first checks its own cache to see if it already knows the IP address for that domain. If not, it asks the operating system, which checks its cache. If the OS doesn't have the answer cached either, it sends a query to a recursive resolver—typically operated by your ISP, though you might have configured a public resolver like Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 or Google's 8.8.8.8.

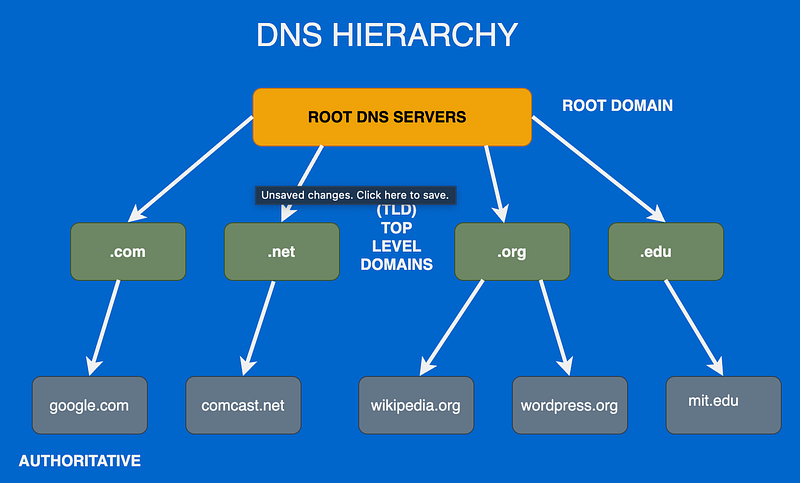

The recursive resolver is where most of the work happens. If it doesn't have the answer cached, it starts a series of queries beginning with one of the 13 root nameservers. These root servers don't know the IP address for your specific domain, but they know where to find the authoritative servers for top-level domains like .com, .org, or .net. The resolver asks the root server, gets directed to the appropriate TLD server, asks that server, and gets directed to the authoritative nameserver for the specific domain you're looking up. Finally, that authoritative server returns the actual IP address, which propagates back through the chain to your browser.

This entire process typically happens in milliseconds, and caching at every level means most queries are answered without going through the full resolution chain. But here's the critical point for understanding encrypted DNS: the encryption we're discussing protects the connection between your device and the recursive resolver. It's the first hop—the part of the journey that traverses networks you don't control, where observers are most likely to be positioned. The resolver's subsequent queries to root servers, TLD servers, and authoritative servers may or may not be encrypted depending on whether you operate your own resolver and how it's configured.

DNS over TLS: The Enterprise-Friendly Option

DNS over TLS, standardized in RFC 7858 back in 2016, takes the straightforward approach of wrapping DNS queries in a TLS tunnel. If you're familiar with how HTTPS protects web traffic, DoT works on the same principle—it establishes an encrypted channel using the Transport Layer Security protocol, then sends standard DNS queries through that protected connection.

The mechanics are relatively simple. Your device opens a TCP connection to the resolver on port 853, performs a TLS handshake to establish encryption and verify the resolver's identity through its certificate, then transmits DNS queries over that encrypted channel. The resolver processes the queries, performs lookups as needed, and returns responses through the same encrypted connection. The connection can persist for multiple queries, avoiding the overhead of repeated handshakes.

Network administrators often prefer DoT for environments they control because it uses a dedicated port. When you see traffic on port 853, you know it's encrypted DNS—nothing else uses that port. This visibility matters for security monitoring, policy enforcement, and troubleshooting. You can easily identify which devices are using encrypted DNS, measure adoption rates, and distinguish DNS traffic from other protocol types in your traffic analysis tools.

However, this visibility cuts both ways. Because DoT uses a distinctive port, it's trivially easy to block. Corporate firewalls, restrictive public WiFi networks, and national internet censorship systems can simply drop traffic on port 853 and prevent DoT from functioning. Users in these environments will find their encrypted DNS queries failing, forcing a fallback to unencrypted DNS or complete resolution failure depending on how their systems are configured.

The TCP requirement also introduces latency compared to traditional DNS over UDP. Every new connection requires a three-way TCP handshake followed by a TLS handshake before any DNS data can flow. Connection reuse mitigates this for subsequent queries, but the initial connection establishment is noticeably slower than a single UDP packet. In practice, users rarely notice this delay because it only affects the first query in a session, but it's a consideration for latency-sensitive applications.

If you want to test DoT connectivity from the command line, the kdig utility (part of the Knot DNS package) provides straightforward syntax:

# Send an encrypted DNS query via DoT

kdig @1.1.1.1 +tls example.com

# Verify TLS certificate details

kdig @1.1.1.1 +tls +tls-ca example.com

These commands are particularly useful for diagnosing certificate validation issues or confirming that DoT is functioning correctly on a given network.

DNS over HTTPS: Privacy Through Ubiquity

DNS over HTTPS, standardized in RFC 8484 in 2018, takes a fundamentally different approach to the blocking problem. Instead of using a dedicated port, DoH embeds DNS queries within standard HTTPS traffic on port 443—the same port used by every secure website on the internet. From a network perspective, DoH traffic looks identical to someone browsing a website.

This design choice has profound implications. Blocking DoH without breaking all HTTPS traffic is essentially impossible. Corporate proxies that allow outbound HTTPS will also allow DoH. National firewalls that permit access to encrypted websites cannot selectively block encrypted DNS without maintaining extensive lists of known DoH resolver endpoints and blocking those specific destinations. Even then, new resolvers can emerge faster than blocklists can be updated.

The technical implementation involves sending DNS queries as HTTP POST or GET requests to a resolver endpoint, typically at a URL like https://1.1.1.1/dns-query. The DNS query data is encoded in either wire format (the same binary format used by traditional DNS) or JSON, included in the HTTP request body or as a query parameter. The resolver returns the DNS response in the same format, wrapped in an HTTP response.

Major browsers have embraced DoH enthusiastically. Chrome versions 83 and later enable DoH by default for users in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, France, and Japan, automatically upgrading to encrypted DNS if the user's configured resolver supports it. Firefox versions 83 and later enable DoH by default for US users, using Cloudflare as the resolver. Safari supports DoH on macOS 11.3 and later and iOS 14.5 and later, though configuration requires installing a profile. Microsoft Edge supports DoH but hasn't enabled it by default.

This browser-level adoption is both a blessing and a challenge for network administrators. Individual users gain privacy protection without any configuration effort—the encryption just happens. But this same automatic behavior can bypass enterprise DNS policies, content filtering, and security monitoring without users or administrators necessarily realizing it. A browser configured to use an external DoH resolver will happily ignore the corporate DNS infrastructure entirely, potentially accessing blocked content, circumventing data loss prevention controls, or evading threat detection systems that rely on DNS visibility.

Testing DoH is slightly more involved than testing DoT because you need to construct proper HTTP requests. Using curl, you can send a query directly:

# Query using DNS over HTTPS (wire format with base64-encoded query)

curl -H "accept: application/dns-message" \

"https://1.1.1.1/dns-query?dns=AAABAAABAAAAAAAAB2V4YW1wbGUDY29tAAABAAE"

The long string in that URL is a base64-encoded DNS query for example.com. For more practical day-to-day testing, Cloudflare's cloudflared utility can run a local proxy that accepts standard DNS queries and forwards them over DoH:

# Start a local DoH proxy on port 5053

cloudflared proxy-dns --port 5053 --upstream https://1.1.1.1/dns-query

# Then query it using familiar tools

dig @127.0.0.1 -p 5053 example.com

This approach lets you use familiar tools like dig against a local port while the actual queries travel encrypted to the upstream resolver.

DNS over QUIC: The Performance-Focused Future

The newest entrant in the encrypted DNS space is DNS over QUIC, standardized in RFC 9250 in 2022. DoQ uses the QUIC transport protocol—the same foundation underlying HTTP/3—which builds TLS 1.3 encryption directly into the transport layer rather than layering it on top of TCP as DoT and DoH do.

QUIC was designed by Google to address the latency problems inherent in TCP-based protocols. Traditional TCP requires a three-way handshake to establish a connection, and adding TLS requires additional round trips for key exchange. QUIC combines connection establishment and cryptographic handshake into a single round trip, and in cases where the client has previously connected to the server, it can send data immediately with zero round trips using a mechanism called 0-RTT.

For DNS queries, which are typically small and latency-sensitive, this performance improvement matters. DoQ can resolve queries faster than DoT or DoH, particularly for the first query in a session or when network conditions cause connection resets. QUIC also handles packet loss more gracefully than TCP, maintaining connection state even when individual packets are dropped and avoiding the head-of-line blocking that can stall TCP streams.

DoQ uses UDP port 853—the same port number as DoT but over UDP rather than TCP. This means it's distinguishable from regular traffic and can be blocked by firewalls that filter on port numbers, similar to DoT. However, the performance benefits may make this tradeoff worthwhile for environments where blocking isn't a concern.

Adoption remains limited compared to DoT and DoH. AdGuard DNS and NextDNS support DoQ, as do a few other privacy-focused resolvers:

# DoQ resolver endpoints

quic://dns.adguard.com

quic://dns.nextdns.io

Browser support is nonexistent at present—you need dedicated client software to use DoQ. But as QUIC adoption grows for web traffic through HTTP/3, the infrastructure and expertise needed to support DoQ will become more widespread. Organizations planning their encrypted DNS strategy should keep DoQ on their radar as a future option, even if it's not practical for immediate deployment.

Configuring Encrypted DNS Across Platforms

Implementation details vary significantly across operating systems and browsers, and understanding these differences helps you plan a deployment that works for your specific environment.

Windows 11 includes native DoH support, accessible through the network settings interface:

Settings → Network & Internet → Wi-Fi (or Ethernet) → DNS server assignment → Edit

You'll see options for "Encrypted only (DNS over HTTPS)" which refuses to fall back to unencrypted DNS, or "Encrypted preferred, unencrypted allowed" which tries DoH first but accepts plaintext responses if encrypted resolution fails. The latter option provides better reliability at the cost of potentially exposing some queries. Microsoft designed this flexibility to accommodate networks where DoH isn't fully functional while still encouraging encryption where possible.

macOS handles encrypted DNS differently, requiring the installation of a configuration profile to enable DoH or DoT system-wide. Apple provides documentation for creating these profiles, or you can use profiles provided by DNS resolver operators. The 1.1.1.1 app from Cloudflare, for example, can install the necessary profile automatically. This profile-based approach gives Apple centralized control over DNS configuration, which aligns with their broader security model but requires more setup than the Windows approach.

Android versions 9 and later support DoT natively through the Private DNS setting:

Settings → Network & Internet → Private DNS

You can enter the hostname of a DoT resolver, and the system will automatically encrypt all DNS queries:

# Common DoT resolver hostnames for Android

dns.google

one.one.one.one

dns.quad9.net

Note that this setting uses hostnames rather than IP addresses, which means Android needs to perform an initial unencrypted DNS lookup to find the resolver's IP—a bootstrap problem that's unavoidable without hardcoding resolver addresses. It's a minor privacy leak but generally acceptable given the protection for all subsequent queries.

iOS 14 and later support both DoH and DoT, but like macOS, configuration requires a profile or a dedicated app. The Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 app, DNSCloak, and NextDNS all provide iOS apps that configure encrypted DNS. These apps typically work by installing a local VPN profile that intercepts DNS queries and forwards them encrypted, which sounds more invasive than it is—the "VPN" in this case only handles DNS traffic, not your general internet connection.

For browsers, the configuration varies by vendor but follows similar patterns:

# Firefox DoH configuration

Settings → Privacy & Security → DNS over HTTPS

# Chrome DoH configuration

Settings → Privacy and Security → Security → Use secure DNS

Firefox offers options to use the default resolver with DoH if supported, use a specific DoH provider like Cloudflare or NextDNS, or disable DoH entirely. Chrome provides a similar toggle with provider selection. Both browsers maintain their own DNS resolution stack separate from the operating system when DoH is enabled, which is why browser-level DoH can bypass system-level DNS configuration.

Enterprise Deployment: Balancing Security and Visibility

Deploying encrypted DNS in an enterprise environment introduces complexities that don't exist for individual users. The fundamental tension is between the privacy benefits of encryption and the visibility requirements of security monitoring and policy enforcement. Most organizations can't simply enable DoH everywhere and accept that they'll lose visibility into DNS traffic.

The starting point for any enterprise deployment is understanding your current DNS infrastructure. Document all resolvers in use, internal and external. Map the query patterns—which applications query which domains, how traffic flows through your network, and where DNS-based security controls are implemented. This baseline tells you what you're working with and what you risk breaking.

Active Directory environments deserve particular attention because they represent a potential minefield for encrypted DNS deployments. Windows domain services rely extensively on DNS for locating domain controllers, finding services, and supporting authentication. Microsoft's DNS servers don't support DoH for these internal queries, and attempting to force encrypted DNS for domain resolution will break things in ways that are painful to troubleshoot. The guidance from Microsoft is clear: domain-joined machines should not enable "Require DoH" for their domain DNS servers. If you need encryption for internal DNS traffic, consider IPsec-based transport encryption rather than protocol-level DNS encryption.

Split-horizon DNS configurations create another challenge that many organizations encounter. This setup maintains separate DNS views for internal and external queries—the same domain name resolves to different addresses depending on whether the query comes from inside or outside the corporate network. When browsers use external DoH resolvers, they bypass the internal DNS infrastructure entirely, potentially breaking access to internal applications or exposing internal addressing to external resolvers. Users might find that applications work fine from the office but fail mysteriously when working remotely with DoH enabled, or vice versa.

The practical solution for most enterprises involves deploying internal encrypted DNS resolvers. Running your own DoH or DoT resolver gives you the encryption benefits while maintaining visibility and control. Your internal resolver can forward queries to external resolvers over encrypted channels, providing end-to-end encryption for external lookups while keeping internal resolution under your control. Browser policies can then configure endpoints to use your internal resolver for DoH, preventing bypass of corporate DNS infrastructure while still providing encryption for the queries that leave your network.

Monitoring for encrypted DNS bypass is also important in enterprise environments. Users may configure personal DoH resolvers in their browsers, intentionally or inadvertently circumventing your DNS policies. Whether you choose to allow, block, or simply monitor this behavior depends on your security requirements and organizational culture. Technical controls can block known DoH endpoints or detect anomalous HTTPS traffic to suspected resolver destinations. Some organizations take a permissive approach, allowing personal DoH use while monitoring for compliance with acceptable use policies. Others block external DoH entirely to maintain DNS visibility.

Choosing Your Resolver Wisely

If you're configuring encrypted DNS for personal use or selecting an external resolver for enterprise deployment, the choice of provider matters more than you might think. Different resolvers offer different privacy policies, performance characteristics, and additional features that can align better or worse with your specific needs.

Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 service emphasizes privacy above almost everything else, committing to never log querying IP addresses and deleting all query logs within 24 hours. Cloudflare operates one of the largest global networks, which generally translates to low latency regardless of your geographic location:

# Cloudflare DNS endpoints

DoT: 1.1.1.1:853 or 1.0.0.1:853

DoH: https://1.1.1.1/dns-query

# Cloudflare with malware blocking

1.1.1.2 / 1.0.0.2

# Cloudflare with malware + adult content blocking

1.1.1.3 / 1.0.0.3

For families or organizations wanting basic protection without managing their own filtering, these variants provide a middle ground.

Google's 8.8.8.8 has been the most widely used public DNS resolver for years, long before encrypted DNS was a consideration. Google does log queries, retaining full data for 24-48 hours and anonymized data longer for analysis purposes. Privacy advocates sometimes object to this logging, though Google argues the data helps them improve the service and detect abuse:

# Google DNS endpoints

DoT: 8.8.8.8:853 or 8.8.4.4:853

DoH: https://dns.google/dns-query

The performance is generally excellent given Google's global infrastructure.

Quad9 at 9.9.9.9 differentiates itself through security-focused filtering. The service blocks known malicious domains by default, providing a layer of protection against malware, phishing, and command-and-control traffic:

# Quad9 DNS endpoints (with threat blocking)

DoT: 9.9.9.9:853

DoH: https://dns.quad9.net/dns-query

# Quad9 without filtering

DoT: 9.9.9.10:853

DoH: https://dns10.quad9.net/dns-query

Quad9 commits to not logging personally identifiable information, and the organization operates as a nonprofit, which some users find reassuring compared to commercial providers.

NextDNS and AdGuard DNS offer customizable filtering and logging policies that go far beyond what the major providers offer. These services let you create profiles with specific blocking rules, view query logs if desired, and configure features like ad blocking at the DNS level:

# AdGuard DNS endpoints

DoT: 94.140.14.14:853

DoH: https://dns.adguard.com/dns-query

DoQ: quic://dns.adguard.com

# NextDNS endpoints (requires account for custom config)

DoT: <config-id>.dns.nextdns.io

DoH: https://dns.nextdns.io/<config-id>

DoQ: quic://dns.nextdns.io

Both support DoQ in addition to DoT and DoH, making them attractive for users who want to experiment with the latest protocols. The configurability makes them ideal for users who want fine-grained control over their DNS behavior without running their own infrastructure.

Troubleshooting When Things Go Wrong

When encrypted DNS doesn't work as expected, systematic troubleshooting helps isolate the issue faster than random experimentation. Connection failures are the most common problem, particularly with DoT. Because port 853 is frequently blocked by corporate networks, public WiFi, and some ISPs, the first diagnostic step is verifying that the port is reachable:

# Test if DoT port is reachable

nc -zv 1.1.1.1 853

If this fails, port blocking is your likely culprit, and you'll need to either work around the block using DoH or accept unencrypted DNS on that network.

Certificate validation failures present differently—the connection establishes but then fails during the TLS handshake. Common causes include system clock skew (TLS certificates are time-sensitive), missing or outdated root certificates, or actual certificate problems on the resolver side:

# Test TLS handshake and view certificate chain

openssl s_client -connect 1.1.1.1:853

# Check your system clock if certificates fail validation

date

Clock skew is surprisingly common in my experience; I've seen systems fail certificate validation because their clocks drifted minutes or hours from reality, particularly on devices that don't regularly sync time or have dead CMOS batteries.

For DoH troubleshooting, browser-specific diagnostic tools help identify configuration and resolution issues. Firefox users can navigate to the network diagnostics page to view DNS resolution status, including whether the Trusted Recursive Resolver (TRR) feature is active:

# Firefox DNS diagnostics

about:networking#dns

# Chrome DNS diagnostics

chrome://net-internals/#dns

Both browsers log DoH failures that can help identify configuration problems, though finding those logs requires some digging through browser debug interfaces.

Performance problems are trickier to diagnose because they can stem from various causes that produce similar symptoms. A geographically distant resolver adds latency to every query, which you might experience as pages loading slowly despite a fast internet connection. Connection reuse failures force repeated TLS handshakes, multiplying latency for each query. Overloaded resolvers respond slowly, though major providers like Cloudflare and Google rarely have this problem. Comparing timing across resolvers helps identify whether the problem is specific to one service or systemic to your network:

# Compare query times across different resolvers

dig @1.1.1.1 example.com +stats | grep "Query time"

dig @8.8.8.8 example.com +stats | grep "Query time"

dig @9.9.9.9 example.com +stats | grep "Query time"

The query time is reported in milliseconds, making it easy to spot resolvers that are significantly slower than others from your location.

Planning a Phased Implementation

For organizations beginning their encrypted DNS journey, a phased approach reduces risk and builds operational experience before committing to widespread deployment. Start by auditing your current DNS infrastructure thoroughly—this baseline documentation proves invaluable when troubleshooting issues later. Identify all resolvers in use, map query flows, and document where DNS-based security controls operate. You might be surprised by what you find; shadow IT DNS configurations are more common than most administrators realize.

Deploy DoT first for managed devices where you control the configuration. The dedicated port makes monitoring straightforward, letting you verify that encryption is working and measure adoption rates. Internal IT devices make good initial candidates because you can respond quickly to any issues, and the users affected are likely to be more tolerant of temporary problems during rollout.

Next, deploy internal DoH resolvers. This gives you the browser-level encryption benefits while maintaining organizational control. Configure browser policies to direct DoH traffic to your internal resolvers rather than external services. This prevents bypass of corporate DNS policies while still encrypting queries. The policy configuration varies by browser and operating system, but most enterprise management tools support the necessary settings.

Exclude domain-joined machines from mandatory DoH for domain DNS servers—this point deserves repeating because getting it wrong causes significant problems. Active Directory depends on traditional DNS for core functionality, and attempting to encrypt this traffic breaks things. If internal DNS encryption is required for compliance, explore IPsec-based protection rather than DoH or DoT.

Monitor continuously for bypass attempts as you roll out encrypted DNS. Users configuring personal DoH resolvers in browsers can circumvent your DNS infrastructure entirely. Whether you block this behavior, allow it, or simply monitor it depends on your security requirements and organizational culture. The technical capability to detect and respond matters regardless of policy.

Finally, keep DoQ on your roadmap for future consideration. As QUIC adoption grows and more resolvers support the protocol, the performance benefits will become increasingly attractive. Building familiarity with QUIC now positions you to adopt DoQ when the ecosystem matures, and you'll be ready to move quickly when the time is right.

The Road Ahead

Encrypted DNS represents a fundamental improvement in internet privacy and security, addressing a vulnerability that's existed since the early days of the network. The question is no longer whether to adopt these technologies but how to implement them in ways that align with your specific requirements and constraints.

For individual users, the path is straightforward—enable DoH in your browser or DoT on your device, select a resolver whose privacy policy you trust, and enjoy encrypted DNS without significant effort. The major browsers and operating systems have made this increasingly seamless, and most users can benefit from encrypted DNS without understanding the technical details.

For enterprises, the path requires more planning but leads to the same destination. The regulatory environment is moving toward mandatory DNS encryption, and early adoption builds the operational experience needed to handle compliance deadlines without crisis-mode implementation. The technical challenges are real but solvable with thoughtful architecture and phased deployment. Starting now gives you time to make mistakes, learn from them, and refine your approach before encryption becomes mandatory rather than optional.

The protocols themselves will continue to evolve in ways we can anticipate and ways we can't. DoQ offers a glimpse of what's next, trading some of DoH's blocking resistance for meaningful performance improvements. New mechanisms like Oblivious DoH add additional privacy layers by separating query content from client identity. Discovery of Designated Resolvers helps clients securely upgrade to encrypted DNS without manual configuration.

Whatever the specific technology, the direction is clear. Plaintext DNS is a legacy of an era when network trust was assumed rather than verified. Encrypted DNS is how we finally fix that assumption, decades later but better late than never. The tools exist, the standards are mature, and the time to implement is now.

---

Further Reading

For those wanting to dive deeper into the technical specifications and implementation guidance, the following resources provide authoritative information. RFC 7858 defines DNS over TLS with all the technical details you'd ever need. RFC 8484 covers DNS over HTTPS comprehensively, and RFC 9250 specifies DNS over QUIC for those interested in the cutting edge. Cloudflare's learning center provides accessible explanations of DNS encryption concepts for those who prefer less formal documentation, and Microsoft's documentation covers DoH client support in Windows Server 2022 for enterprise deployments requiring integration with Microsoft infrastructure.

Share this article

Comments

Comments are powered by GitHub Discussions via Giscus.

To enable comments, configure Giscus at giscus.app and update the Comments component with your repo settings.